March 31, 2009

March 30, 2009

they never run, only call

I meant to write about Rachel Goodyear’s superb show “they never run, only call” at International 3 http://www.international3.com/exhibition.php?E=40 while it was still on but didn’t get round to it. But I have been carrying the experience around with me of her intense concentration of the drawings since I saw it. And this was magnified the other day when I happened to be in Manchester Art Gallery for the launch of Manchester International Festival – of which more in future posts. No, the specific trigger for reconsidering Goodyear was seeing the Gallery’s newest acquisition Antony Gormley’s Filter (pictured). “It’s a hanging figure made of flat mild steel rings welded together. The sculpture is hollow and holes in the rings allow you to glimpse inside the body, which contains a suspended heart.”

I meant to write about Rachel Goodyear’s superb show “they never run, only call” at International 3 http://www.international3.com/exhibition.php?E=40 while it was still on but didn’t get round to it. But I have been carrying the experience around with me of her intense concentration of the drawings since I saw it. And this was magnified the other day when I happened to be in Manchester Art Gallery for the launch of Manchester International Festival – of which more in future posts. No, the specific trigger for reconsidering Goodyear was seeing the Gallery’s newest acquisition Antony Gormley’s Filter (pictured). “It’s a hanging figure made of flat mild steel rings welded together. The sculpture is hollow and holes in the rings allow you to glimpse inside the body, which contains a suspended heart.”During his siting visit, Gormley said “The work hangs in space as if in orbit, open to light and the elements, it is a meditation on the relationship between the core of the body and space at large... It suggests that, while movement, freedom of choice and the exercising of will is one way in which life expresses itself, there is another axis: the relationship between emotion and spatial experience." I was particularly struck by these comments in part because my next book “Space” is examining these very questions; but as I say, when I say Gormley’s metal sausage, Rachel Goodyear became an even stronger presence. The work itself I have already dismissed formally with the reference to metal products; but the sculptors claims for his work are more interesting because of what they tell us. Some of the chaff can be cleared straight away: it is not open to the elements because it is in an environmentally enclosed atrium. There is no suggestion of orbit or movement because it is suspended at a height, relation to other structures (lifts, staircases, etc) in the space and angle to suggest stasis not movement. And then the two claims that it suggests 1) movement, freedom of choice etc are herein represented. 2) that there is a relationship between emotion and spatiality. The first one hardly needs repeating – there figure is static. It’s casing with arms at its side and legs together suggest no internally generated motion (something you would expect even a subtle indication of if you were going to claim a relationship between the internal emotion and the external space), and as already noted there is no external motion either; it can’t even be said to hover in the space as it quite clearly hangs, nor is there dynamics that move it because you can see stablizing wires so there is no suggestion of imbalance or spin. But, as if to anticipate formal critique of the metal sausage, Gormley says: "My work continues to be misinterpreted as some form of representational art. It's useless if you take it as that. It's an invitation for you to think of yourself being there, an invitation for you to think of those moments when you are, like it is, detached from the flow of everyday life. We're always doing something, fulfilling some kind of command, some kind of duty, some kind of work and this piece is trying to think of a human being as being not doing." That is dangerous ground for Gormley to tread because this claim of existentialism invites not a location as representational art but rather a comparison with artists who could actually make work that coalesces being, such as Giacometti. However, I think there is a way in which Gormley’s self-casts engage with “the flow of everyday life. We're always doing something, fulfilling some kind of command, some kind of duty, some kind of work”; in the context of the UK’s regimental institutionalising ontology Gormley’s work does say something to us: it is the apotheosis of the mediocrity expected of us; as (most of) his oeuvre are casts of himself, they represent are our standardisation, but without ontological insight the artist, mediocre himself, this New Banality to which we are directed to aspire is writ dismal and large which ultimately is more denigrating than hopelessness. Gormley’s planned installation for the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square, http://www.london.gov.uk/fourthplinth/plinth/gormley.jsp, “One & Other” inadvertently but openly displays this for all to see. No doubt it will be surrounded by some bollocks of celebrating ordinary people (in the context of the imperial sculptural landscape of the square) but actually what it does is offer up our interchangeability and therefore lack of value. No doubt the selected 2400 people will have be unutterably worthy New Labour diversity, but I find the safety net around the plinth the hilarious Health & Safety coda – the work celebrates its absence of artistic and physical risk.

Criticising Antony Gormley is really too easy to take so much space, ordinarily I wouldn’t give it brain space. It was the context of remembrance of Rachel Goodyear’s show – even the title “they never run, only call” could be a description of establishment artists such as Gormley (or Motion and Armitage for that matter). But to mobilise her to that cause would be a disservice and a paltry use for something so powerful. It may seem strange to compare stodgy metal sculpture with fine small scale drawings, but it is an ontological comparison: Goodyear’s investigations are mystical, edgy, humorous and sexy, desperate and transcendent. Even ontological grounds though, it is still an unfair and unnecessary comparison: Goodyear is fascinating and Gormley is Official stodge.

So what was the other thing that bothered me? It is the same underlying problem in the Manchester International Festival, the launch for which I was in the city gallery and will write on in more depth in another blog.

March 24, 2009

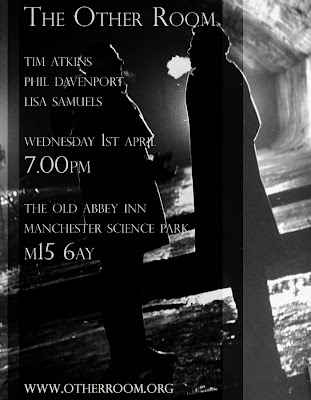

The Other Room Anthology

The Other Room Anthology 08/09 is now available, featuring:

David Annwn

Richard Barrett

Caroline Bergvall

Stuart Calton

Lucy Harvest Clarke

Patricia Farrell

Alan Halsey

Tom Jenks

Alex Middleton

Geraldine Monk

Maggie O’Sullivan

Robert Sheppard

Harriet Tarlo

Scott Thurston

Tony Trehy

Carol Watts

Joy As Tiresome Vandalism

The official launch is at the next Other Room on 1st April but you can pre-order a copy for £5 + £0.75 P&P via PayPal by visiting us at www.otherroom.org.

David Annwn

Richard Barrett

Caroline Bergvall

Stuart Calton

Lucy Harvest Clarke

Patricia Farrell

Alan Halsey

Tom Jenks

Alex Middleton

Geraldine Monk

Maggie O’Sullivan

Robert Sheppard

Harriet Tarlo

Scott Thurston

Tony Trehy

Carol Watts

Joy As Tiresome Vandalism

The official launch is at the next Other Room on 1st April but you can pre-order a copy for £5 + £0.75 P&P via PayPal by visiting us at www.otherroom.org.

March 16, 2009

Great Cinema

While Glen Ford would be respected as one of the movie greats, it amazes me that no one mentions one stunning performance which I regard as the greatest death scene in cinema history. Ordinarily most people would quickly change the channel when the first Christopher Reeve Superman movie comes on the TV, but I am riveted to the screen (as I was last night) until Ford's scene. He plays Jonathan Kent and only has two scenes in the film - the first one the Kent's find the baby superman just arrived from Krypton and in the second he puts a fatherly arm around the Clark's teenage shoulders and speculates about whether there is some cosmic purpose to the boy being 'super'. The conversation ends and Clark runs ahead to the barn calling back "race you". The camera turns onto Ford as he walks up the slope. His heart attack happens in seconds, if you blink you could miss it, but it is, I think, unbearably moving. A realisation passes across his face, then a panic but slight because there is no time, he grips his wrist, and simply says: "oh no". And he is dead. The subtlety of his performance is appalling.

March 14, 2009

Small Eternities

It's always a pleasure to visit Manchester's finest building - the Rylands Library. The recent refurbishment is thankfully sufficiently restrained so as not to interfer with the original architecture. The Library itself has got a fabulous collection including 500-year-old translations of the Bible into English, one of England’s oldest recipe books and even fragments of the Gospel of Mary. Its poetry collection stretches from one of the earliest existing manuscripts of the complete Canterbury Tales by Chaucer to the Dom Sylvester Houédard http://www.archiveshub.ac.uk/news/0310hou.html plus, as the local publisher, the Carcanet archive.

It's always a pleasure to visit Manchester's finest building - the Rylands Library. The recent refurbishment is thankfully sufficiently restrained so as not to interfer with the original architecture. The Library itself has got a fabulous collection including 500-year-old translations of the Bible into English, one of England’s oldest recipe books and even fragments of the Gospel of Mary. Its poetry collection stretches from one of the earliest existing manuscripts of the complete Canterbury Tales by Chaucer to the Dom Sylvester Houédard http://www.archiveshub.ac.uk/news/0310hou.html plus, as the local publisher, the Carcanet archive.The Library has recently opened an exhibition called "A Small Eternity - the Shape of the Sonnet Through Time" which I was keen to see as the form has been recently illuminated by Jeff Hilson's brilliant survey of contemporary practice "The Reality Street Book of Sonnets". Sad to report the best you can say about the show is that it is how an archivist curates. In terms of the content, the piece that really caught my eye was an illuminated page by Petrarch:

"You who hear the sound, in scattered rhymes"

You who hear the sound, in scattered rhymes,

of those sighs on which I fed my heart,

in my first vagrant youthfulness,

when I was partly other than I am,

I hope to find pity, and forgiveness,

for all the modes in which I talk and weep,

between vain hope and vain sadness,

in those who understand love through its trials.

Yet I see clearly now I have become

an old tale amongst all these people, so that

it often makes me ashamed of myself;

and shame is the fruit of my vanities,

and remorse, and the clearest knowledge

of how the world's delight is a brief dream.

I was pleased to stumble on this piece first because as the display unfolds it comes more and more annoyed under the malign and banal influence of Carcanet and the Centre for New Writing at Manchester University (of which the libary is part). Apart from the New Labour access approach to curatorship, it is generally acknowledged that labels larger than the object/work to which they refer is bad curatorial practice. It is admittedly a challenge to exhibit book based works, especially rarely valuable ones, because their contents remain for the most part (except for the displayed page) out of reach, but photocopy enlargement of some pages isn't the answer; colour photocopies of Carcanet cover designs isn't the answer. Small Eternity is a typical 'book-on-the-wall' show made worse by the dismally low level of interpretation intelligence - in a glass case we find photocopied and laminated sheets featuring annotated Petrarchian, Spenserian and Shakespearian sonnets, but the Petrarch (above) clearly features symbolic and paleo-Oulipian devices in the illumination and no formal interpretation is offered bar the identification of a little drawing of Laura (his unrequited love). The only poem that actually works as an exhibit is Edwin Morgan's concrete poem: Opening the Cage: 14 Variations on 14 Words: 'I have nothing to say and I am saying it and that is poetry.

The really problematic aspect of Small Eternity is the complete absence of any sense that the Sonnet has potential as a contemporary form as the Hilson anthology demonstrates. In one corner there is a intimate seating area a small table has a small selection of "How to" books with paper and pencils and the invitation to write your own sonnet. Then you can pin it on a board and then other visitors can put up other cards that say "I like this one" - the winner of the popular vote (and everyone who voted) will get a handprinted version of the poem. Although I suppose banal in its own right, the participatory aspect sits neatly with the shadow of Carcanet/Manchester Writing School. This School of Quietude has produced a small anthology of Sonnets by current students whose lack of poetic artifice can only draw a rather resigned sigh.

March 06, 2009

Altermodern

In responding to the Tate Triennial exhibition, Altermodern, you are forced to approach it within the framing logic laid out by its French curator Nicolas Bourriaud.

http://www.tate.org.uk/britain/exhibitions/altermodern/

“Altermodern is an in-progress redefinition of modernity in the era of globalisation, stressing the experience of wandering in time, space and mediums”. A mighty claim – re-defining modernity – which adding “in-progress” doesn’t release the exhibition from the responsibility to deliver. Of course it can’t and doesn’t. So you have to wonder why Bourriaud made the claim for the show. To answer this you have to turn to the catalogue essay (or the video clips on the website if you like). It is reasonable given the context of curating in one of the international institutional galleries and of the implied portentous status of a Triennial for Bourriaud set out to consider the historic moment of globalisation, liberal uncertainty, fundamentalisms, etc, we are in and where contemporary art can and is going. To an extent one should expect that these contexts invite, even demand a vision-driven manifesto as the appropriate response to the situation – but Bourriaud doesn’t have the insight to do it – hence “in-progress” and an essay so lacking in rigour or even simple logical flow that it leaves the reader in disbelief.

So what is Bourriaud’s Altermodern? “Altermodern can be defined as that moment when it became possible for us to produce something that made sense starting from an assumed heterochrony, that is, from a vision of human history as constituted of multiple temporalities, disdaining the nostalgia for the avant-garde and indeed for any era – a positive vision of chaos and complexity. It is neither a petrified kind of time advancing in loops (postmodernism) nor a linear vision of history (modernism), but a positive experience of disorientation through an art-form exploring all dimensions of the present, tracing lines in all directions of time and space.” I find this problematic. Although globalisation is clearly epochal, I don’t see how that or the artists featured in the show posit a vision of history constituted as multiple temporalities – partially because none of the artists convincingly present work up to the moment’s challenge and partially because ‘multiple temporalities’ doesn’t mean anything outside a Star Trek (Next Generation) episode. Trying to unpick the idea, I guess it relates to the Glass Bead Game phenomenon of the web’s universal knowledge offer – that artists can reference and respond to any other culture or time via the net. This hardly constitutes a vision of human history unless you use a definition of history which isn’t historical. I also question whether this is the moment when it has become possible to do it, as I can think of many artists and writers who have had a vision of human history constituted in multiple temporalities – the first that jumps to mind is Claude Simon, specifically Triptych, written in 1973 – so this would be a long moment we are in. Then we have the disdain for the nostalgia for the avant-garde. I am not sure whether this means that altermodernism re-embraces the avant-garde or whether it is only the nostalgia it turns its nose up at. It is probably to be read that to be (alter)modern you should disdain the avant-garde and the nostalgia – interesting that ‘multiple temporalities’ doesn’t take into account past pain (Greek nostos, a return home; algia – pain). Bourriaud is probably right to disconnect altermodern from the notion of an avant-garde because there is no sign of any dramatic leap or direction in any of the work in the show. Does one contradict or collude with the altermodern by favouring a multiple temporality which valorises ‘Make it new’, I wonder? And speaking of nostalgia, his "positive experience of disorientation" sounds remarkably like Keatsian negative capability.

Altermodern is also characterised as “trajectories have become forms: contemporary art gives the impression of being uplifted by an immense wave of displacements, voyages, translations, migrations of objects and beings, …displacement has become a method of depiction …artistic styles and formats must henceforth be regarded from the viewpoint of diaspora, migration and exodus.” While travel in the modern world is easier than anytime in history, surely historically modernism can lay claim to the effect of displacements and voyages with the more convincing imperative of wars. I think displacement as depiction is nonsensical and it is annoying when theorists who don’t actually make works use ‘must’ and limit the field of creative action. Why must artistic production be regarded from these viewpoints? This is as arbitrary as saying that the only legitimate subject for poetry is climate change.

This is a moment of history, but “this synthesis ‘altermodernism’” does not address the spirit or needs of the time because it is an argument without sense or substance.

At the end, Bourriaud’s essay closes the door to the field in which the break will come: Out of the blue J.M.G. Le Clézio is quoted: “When they created cities, when they invented concrete, tar and glass, men created a new jungle – but have yet to become its inhabitants. Maybe they will die out before recognising it for what it is. The [Amazonian] Indians have thousands of year’s experience of it, which is why their knowledge is so perfect. Their world is not different from ours, they simply live in it, while we are still in exile”. This passage is jaw-dropping nonsense: who are ‘they’ who created these cities? How far back in history is he locating this? Concrete inventors? Is that the Romans he means? Tar wasn’t invented; it occurs naturally and has been used since the Iron Age. Glass, another ancient product. How can ‘men’ not yet be inhabitants of the city when more than half of the world’s population lives in cities? The city is actually a human and productive focus, just the interconnected node in a network that Bourriaud’s theory needs to have anything to say about the future, but he goes for the nonsensical metaphor of the archipelago. Le Clézio simply updates the Romantic, the picturesque jungle, the noble savage. Let’s see how perfect the Amazonian Indian’s knowledge is when the loggers have chopped down the forest! I don’t know this writer but the footnote indicates publication in Paris. Having just returned from Paris, I can report that it is not a new jungle. Maybe this is an example of what Bourriaud meant when he talked about an assumed heterochrony, i.e. a Glass Bead Game of historical reference that is so jumbled as to be without logic. So with this irrational pejorative characterisation of the City, Bourriaud misses the aspect of globalisation with which artists can and are engaging with the spatial and temporal dilemmas and challenges of 21st Century capitalism. This is staring Bourriaud in the face actually – of the 28 artists listed in the catalogue all but one live and work in cities (not jungles).

And the exhibition? The only work that really held its own was Tacita Dean’s Russian Endings, which coincidently I showed in Bury Art Gallery in 2007 (pictured).

http://www.tate.org.uk/britain/exhibitions/altermodern/

“Altermodern is an in-progress redefinition of modernity in the era of globalisation, stressing the experience of wandering in time, space and mediums”. A mighty claim – re-defining modernity – which adding “in-progress” doesn’t release the exhibition from the responsibility to deliver. Of course it can’t and doesn’t. So you have to wonder why Bourriaud made the claim for the show. To answer this you have to turn to the catalogue essay (or the video clips on the website if you like). It is reasonable given the context of curating in one of the international institutional galleries and of the implied portentous status of a Triennial for Bourriaud set out to consider the historic moment of globalisation, liberal uncertainty, fundamentalisms, etc, we are in and where contemporary art can and is going. To an extent one should expect that these contexts invite, even demand a vision-driven manifesto as the appropriate response to the situation – but Bourriaud doesn’t have the insight to do it – hence “in-progress” and an essay so lacking in rigour or even simple logical flow that it leaves the reader in disbelief.

So what is Bourriaud’s Altermodern? “Altermodern can be defined as that moment when it became possible for us to produce something that made sense starting from an assumed heterochrony, that is, from a vision of human history as constituted of multiple temporalities, disdaining the nostalgia for the avant-garde and indeed for any era – a positive vision of chaos and complexity. It is neither a petrified kind of time advancing in loops (postmodernism) nor a linear vision of history (modernism), but a positive experience of disorientation through an art-form exploring all dimensions of the present, tracing lines in all directions of time and space.” I find this problematic. Although globalisation is clearly epochal, I don’t see how that or the artists featured in the show posit a vision of history constituted as multiple temporalities – partially because none of the artists convincingly present work up to the moment’s challenge and partially because ‘multiple temporalities’ doesn’t mean anything outside a Star Trek (Next Generation) episode. Trying to unpick the idea, I guess it relates to the Glass Bead Game phenomenon of the web’s universal knowledge offer – that artists can reference and respond to any other culture or time via the net. This hardly constitutes a vision of human history unless you use a definition of history which isn’t historical. I also question whether this is the moment when it has become possible to do it, as I can think of many artists and writers who have had a vision of human history constituted in multiple temporalities – the first that jumps to mind is Claude Simon, specifically Triptych, written in 1973 – so this would be a long moment we are in. Then we have the disdain for the nostalgia for the avant-garde. I am not sure whether this means that altermodernism re-embraces the avant-garde or whether it is only the nostalgia it turns its nose up at. It is probably to be read that to be (alter)modern you should disdain the avant-garde and the nostalgia – interesting that ‘multiple temporalities’ doesn’t take into account past pain (Greek nostos, a return home; algia – pain). Bourriaud is probably right to disconnect altermodern from the notion of an avant-garde because there is no sign of any dramatic leap or direction in any of the work in the show. Does one contradict or collude with the altermodern by favouring a multiple temporality which valorises ‘Make it new’, I wonder? And speaking of nostalgia, his "positive experience of disorientation" sounds remarkably like Keatsian negative capability.

Altermodern is also characterised as “trajectories have become forms: contemporary art gives the impression of being uplifted by an immense wave of displacements, voyages, translations, migrations of objects and beings, …displacement has become a method of depiction …artistic styles and formats must henceforth be regarded from the viewpoint of diaspora, migration and exodus.” While travel in the modern world is easier than anytime in history, surely historically modernism can lay claim to the effect of displacements and voyages with the more convincing imperative of wars. I think displacement as depiction is nonsensical and it is annoying when theorists who don’t actually make works use ‘must’ and limit the field of creative action. Why must artistic production be regarded from these viewpoints? This is as arbitrary as saying that the only legitimate subject for poetry is climate change.

This is a moment of history, but “this synthesis ‘altermodernism’” does not address the spirit or needs of the time because it is an argument without sense or substance.

At the end, Bourriaud’s essay closes the door to the field in which the break will come: Out of the blue J.M.G. Le Clézio is quoted: “When they created cities, when they invented concrete, tar and glass, men created a new jungle – but have yet to become its inhabitants. Maybe they will die out before recognising it for what it is. The [Amazonian] Indians have thousands of year’s experience of it, which is why their knowledge is so perfect. Their world is not different from ours, they simply live in it, while we are still in exile”. This passage is jaw-dropping nonsense: who are ‘they’ who created these cities? How far back in history is he locating this? Concrete inventors? Is that the Romans he means? Tar wasn’t invented; it occurs naturally and has been used since the Iron Age. Glass, another ancient product. How can ‘men’ not yet be inhabitants of the city when more than half of the world’s population lives in cities? The city is actually a human and productive focus, just the interconnected node in a network that Bourriaud’s theory needs to have anything to say about the future, but he goes for the nonsensical metaphor of the archipelago. Le Clézio simply updates the Romantic, the picturesque jungle, the noble savage. Let’s see how perfect the Amazonian Indian’s knowledge is when the loggers have chopped down the forest! I don’t know this writer but the footnote indicates publication in Paris. Having just returned from Paris, I can report that it is not a new jungle. Maybe this is an example of what Bourriaud meant when he talked about an assumed heterochrony, i.e. a Glass Bead Game of historical reference that is so jumbled as to be without logic. So with this irrational pejorative characterisation of the City, Bourriaud misses the aspect of globalisation with which artists can and are engaging with the spatial and temporal dilemmas and challenges of 21st Century capitalism. This is staring Bourriaud in the face actually – of the 28 artists listed in the catalogue all but one live and work in cities (not jungles).

And the exhibition? The only work that really held its own was Tacita Dean’s Russian Endings, which coincidently I showed in Bury Art Gallery in 2007 (pictured).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Fluents (dyslexia)

screenshot of Fluents (dyslexia) Fluents (dyslexia) Through his visit last year, Christian Bök introduced me to creative nexus Noah Pred...

-

As per the last blog, the first novel of my post-UK period, The Family Idiots , is near enough finished (just proofing, etc) so I have mov...

-

Back in 2005, I launched the International Text Festival in Bury, Manchester. It's aim was to question, curate, display, distribute, ar...

-

Having done virtually no research about Leiria before I arrived, I was very enamored with it - a very charming little town, given what I im...